Climatic changes as a result of increases in global average temperature since pre-industrial times are a concern to societies around the world. Estimates are that global temperatures are approximately 1.1 degrees Celsius higher today than pre-industrial times. Climate change can lead to increased risks that impact animal agriculture, such as increases in high precipitation events and droughts, and increased frequency of heat waves.

Scientific evidence strongly points to increases in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG), such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, and nitrous oxide, as the key driver to increased global average temperatures. Consequently, there has been increased focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions from human-activities to halt the increases or potentially lower the concentrations of these heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere.

In the 2015 Paris Agreement, most nations in the world committed to limit global warming to 2.0 or ideally below to 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century compared to pre-Industrial times. Since that agreement, there’s been an increase in commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions or achieve so-called net zero from meat, dairy, and poultry companies.

With the increased discussion of “net zero”, it’s critical to define what this term really means from a scientific perspective.

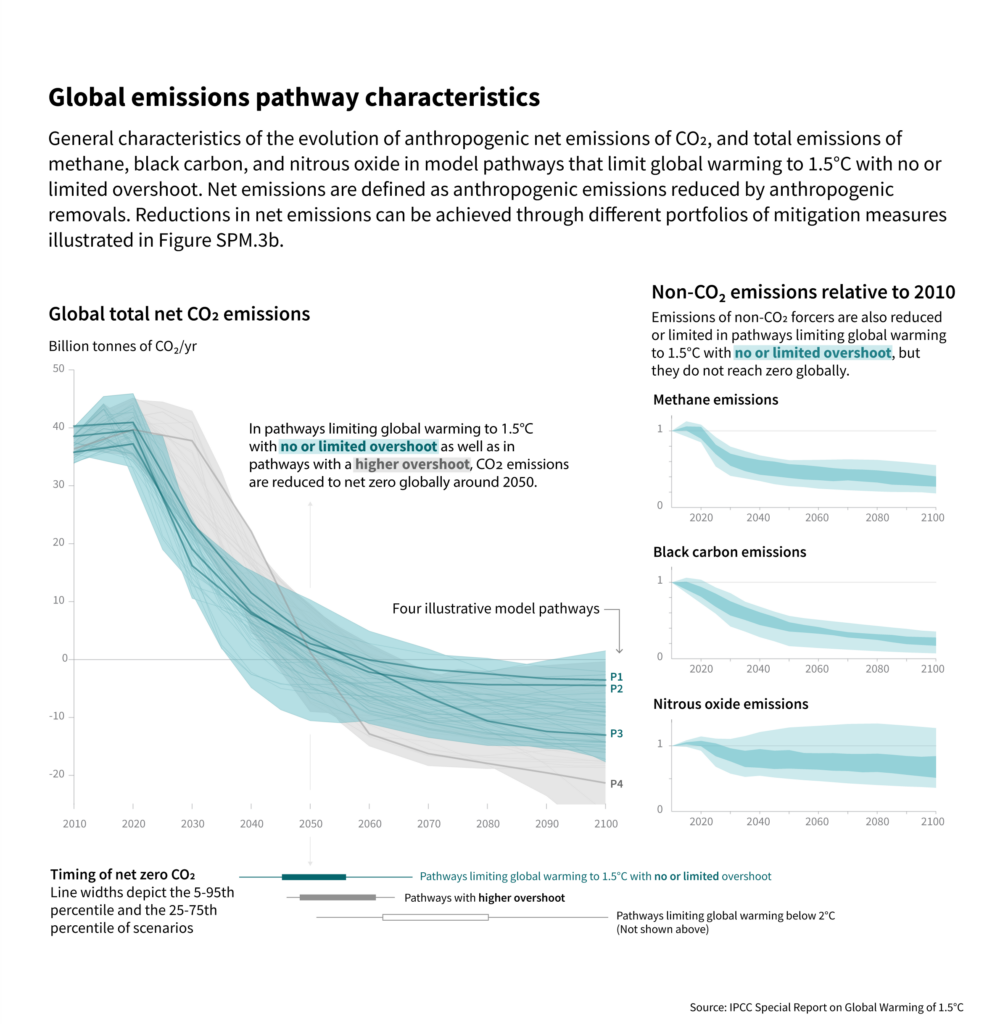

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated that, “Reaching and sustaining net zero global anthropogenic CO2 emissions and declining net non-CO2 radiative forcing would halt anthropogenic global warming on multi-decadal times scales.” In plain language, the first part of this sentence means carbon dioxide emissions from human activities (anthropogenic) must be reduced to zero and/or carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere must balance to result in no net addition of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Simply, we can think of this as a carbon dioxide balance sheet, with both assets (carbon dioxide removal) and liabilities (carbon dioxide emissions from human activities) at the same value. Until the two sides of the balance sheet match, warming will continue.

The second half of the sentence from the IPCC is less straightforward to understand, but highly relevant to animal agriculture as most of the greenhouse gas emissions that come from the production of meat, milk, and eggs are the non-CO2 greenhouse gases, methane and nitrous oxide. “Radiative forcing” refers to the energy or heat that is trapped in the atmosphere. What is unique about non-CO2 gases such as methane is that human caused emissions do not need to reach zero to achieve declining warming or radiative forcing, though emissions of those greenhouse gases must be reduced significantly. The decline in methane emissions particularly depends upon other assumptions, such as how fast CO2 emissions decline, but reductions of 30-50% in 2050 relative to 2010 are likely required to stay with a global average temperature increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius or less.

Many companies have set net-zero targets which means that their production must balance getting their products to the consumer base while also meeting climate reduction targets. In animal agriculture this means striving to achieve net zero CO2 emissions and strong reductions in methane and nitrous oxide emissions. Strong reductions require new innovations such as genetic selection and feed additives to reduce enteric methane emissions naturally produced by ruminant animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Such innovations should also make financial sense to livestock producers and be practical and scalable to achieve net zero ambitions. However, enteric methane emissions cannot ever be zero – biologically, this is likely an impossibility, and as stated above, also unnecessarily to halt global temperature increases. This subtle distinction is critical to understand in animal agriculture – we need to create practical, financial-viable, and scalable solutions to reduce methane emissions, but zero methane emissions is not required to achieve “net zero”.

IPCC Graphic Explaining Global Emissions:

Dr. Sara Place

AgNext Associate Professor of Feedlot Systems