In order to create sustainable animal agriculture practices that benefit climate action, it is important to understand the greenhouse gases involved in beef production. There are three main gasses associated with animal agriculture: carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane. Of these emissions, methane is the most potent greenhouse gas. This is because it has a Global Warming Potential (GWP) 28 times higher than carbon dioxide.

Because methane is a highly potent gas, it traps heat in the atmosphere more effectively than carbon dioxide. But methane is also a short-lived gas, meaning it does not remain in the atmosphere for long durations. Interested in learning more about the EPA’s Emissions Inventory? Read this blog.

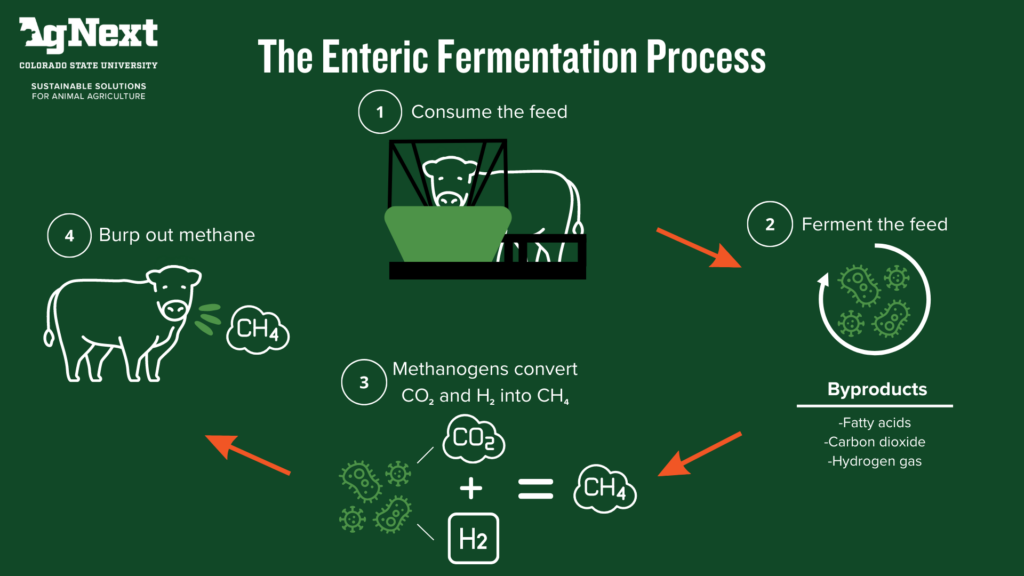

In animal agriculture, it is important to study methane because it is produced by ruminate animals such as cattle, sheep, and other domesticated farm animals. These animals have a rumen microbiome in their digestive system that ferments the feed they consume, which later gets released into the atmosphere as methane through burps. This fermentation process produces what researchers call enteric methane, because it is produced in the intestines of the animal.

The whole enteric fermentation process relies on the microbes within the rumen’s digestive environment. The microbes found in this process are classified as methanogens which feed off of the byproducts that are produced by the fermentation of feed. Those byproducts include: fatty acids, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen. As the fermentation takes place, and the methanogens ingest the feed byproducts, methane is then released to finish the cycle.

Since methane is produced from fermented feed, the potency relies on the feed intake the animals receive. Considering this, researchers are looking for ways to lessen methane emissions and make them more energy efficient for the animal by altering the animals feed with different ingredients and/or additives.

One way that a more energy efficient diet can be achieved is through feeding ruminants more grain or more carbohydrates because it prevents the animals from producing more hydrogen within the microbiome, therefore lessening the concentration of methane and allowing for the animals to store more energy from remaining hydrogen in the system.

While altering the feed intake is a large component to reducing methane emissions in cattle, there are many more methods being developed that can benefit this research. Researchers at AgNext are looking into possibilities in genetics that prove insights into more energy efficient animals that naturally emit less methane.

Through all of this, it is important to understand that in the beef industry, methane emissions will never reach zero, but the research and implementation can allow for more opportunities to make it an even more sustainable practice. That is why it is important to evaluate the rumen and microbiomes to create more effective solutions in the future.

Julia Giesenhagen

Multimedia Intern

Dr. Sara Place

Associate Professor of Feedlot Systems