Large herbivores frequently make foraging decisions that ensure forage intake is adequate to meet metabolic requirements while maintaining herd cohesion as highly-social animals. For instance, plains bison grazing a matrix of meadows within the boreal forest of Saskatchewan remember important information about the location and quality of forest meadows (Merkle et al. 2014). The animals then use this information to selectively move to meadows of higher benefit, including more energy intake. Further, this tactic was common when bison chose high-quality meadows they had previously visited. It became even more common in their grazing patterns when previously visited meadows were of low quality. This work suggested that free-ranging bison use memory to reduce uncertainty in attaining food requirements.

Plains bison (Bison bison bison) at Konza Prairie Biological Station, Manhattan, KS. Credit: E. J. Raynor.

Now, given the theme of this blog, you might be considering how the test of cognitive theory in foraging ecology and bison herds informs sustainability. This is a curious question indeed. Here is what researchers recently discovered in a recent study with beef cattle (Bos taurus taurus).

These findings on bison in Saskatchewan may help explain the performance benefits of traditional rangeland management (TRM) over adaptive multipaddock management (AMP) in the shortgrass steppe of Colorado in the Western North American Great Plains, a semiarid rangeland ecosystem. In this region of the United States, TRM is practiced through continuous, season-long grazing of a single paddock (or pasture) by a small non-rotational cattle herd. In contrast, AMP grazing rotates a large herd across several paddocks in a grazing season. The latter grazing strategy exposes animals to grazing a single paddock over a short period of time (i.e., a few weeks) instead of an entire 5-month grazing season. How AMP or TRM grazing may mediate the use of cattle memory currently remains unknown to this day.

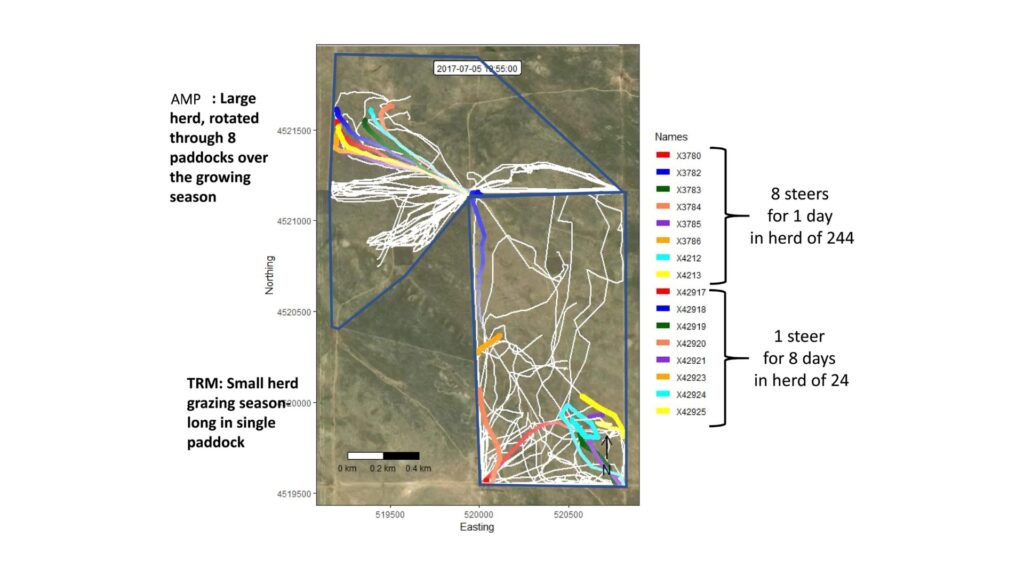

In a first-of-its-kind decade-long study to compare TRM vs. AMP grazing, USDA Agricultural Research Service researchers at the Central Plains Experimental Range reported TRM steers spent more time than adaptively rotated AMP steers in preferred patches within a paddock and foraged in more circular patterns (Augustine et al. 2023). In contrast, steers under rotational grazing management moving from paddock to paddock exhibit less selective foraging by forming a “grazing front” (Fig. 1). The front of the foraging steers moves across the paddock in a homogenous manner that distributes grazing pressure more uniformly. This behavioral adjustment to being in the new pasture was shown to be maladaptive for steer performance when compared to steers stocked season-long regardless of a year’s precipitation or forage production level. On average, over the five-year study, herds managed with continuous, season-long TRM stocking gained 14% more weight by season’s end than an AMP herd managed with adaptive rotations across paddocks. This finding of increased gain on semiarid rangeland in the growing season may extend to informing the duration of their stay at a feedlot for finishing; heavier animals may require less time for finishing, and less time finishing requires less feed purchased. However, many questions remain unanswered from a sustainability and economic perspective. For example, impacts on carcass weights and quality from the various strategies need to be evaluated. Further, the financial outcomes across various sectors (e.g., cow/calf, stocker, feeding) need to be documented prior to the recommendation of widespread adoption of this strategy. The AgNext team plans to address these remaining questions through a series of grazing experiments over the next several growing seasons.

Figure 1. Modified after Augustine et al. 2023. Movement patterns of steers in an AMP vs. a TRM paddock during July, 2017. Blue lines show the boundaries of a pair of 320-acre paddocks, where the upper paddock received the AMP treatment and lower paddock received the TRM treatment. The video shows movements of 8 steers on 1 day (July 5, 2017) in the AMP paddock, in comparison to 1 steer for 8 days (July 1–5 and July 7–9, 2017) in the TRM paddock. A video clip is available below and online here.

Dr. EJ Raynor

Research Scientist