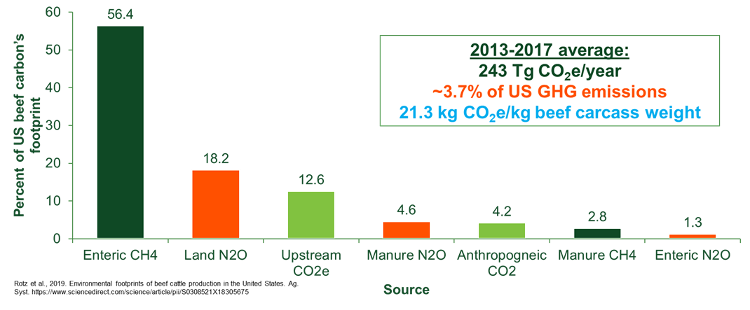

In the coming years, new feed additive solutions to reduce enteric methane emissions will likely become available to cattle feeders. Indeed, the FDA has recently announced it is encouraging developers of additives with environmental claims to engage them early in the development process. Most of these feed additives will aim to reduce enteric methane emissions per animal per day, creating the opportunity to demonstrate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions from the beef supply chain. The focus on mitigating enteric methane emissions is because those emissions represent 56% of the US beef carbon footprint (Figure 1) and mitigating methane can reduce temperature impacts of the beef industry more quickly than other greenhouse gases.

While it is exciting that new feed additive technologies may be available, realistically, these technologies need to make economic sense to become adopted in the industry at large. The economics of mitigating methane also become more challenging if feed additives do not have any animal performance (e.g., improvement of gain) co-benefits. As a result, to make feed additives a break-even proposition or profitable, other income streams, such as carbon credits, will likely need to be available.

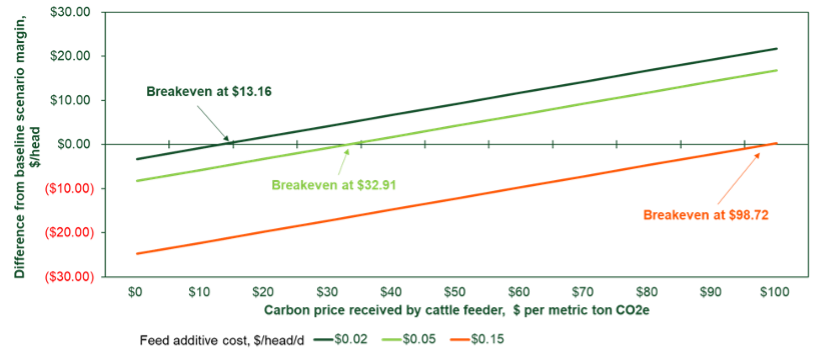

To explore these possible economic scenarios, the AgNext Beef Feed Additive Calculator Tool (FACT) has been developed. This tool can help estimate baseline methane emissions from fed beef cattle per day and over the entire feeding period based on diet characteristics. AgNext’s FACT for Beef also allows the user to enter costs, animal performance impacts, and methane mitigation potential of a feed additive of interest. Finally, the user may also define the carbon price, expressed as USD$ per metric ton. The carbon price represents a price to be paid to the cattle feeder to compensate them for the methane reduction asset created through the feeding of the hypothetical additive.

To put this concept together, we can examine scenarios for a feed additive that reduces enteric methane emissions by 50% with no effect on animal performance at three price points for the additive: $0.02, $0.05, and $0.15 per head per day. As is demonstrated in Figure 2, the breakeven carbon price a cattle feeder must receive varies depending upon the feed additive cost. Even at a cost of only $0.02/head per day, the breakeven carbon price is higher than current voluntary carbon prices, which are currently below $3 per metric ton of CO2e.

The bottom line is compensation for enteric methane reduction will be paramount to adoption of future feed additives with mitigation potential by the beef cattle industry. This will likely require the development of markets for enteric methane reductions and associated monitoring, reporting, and verification systems to ensure confidence in a marketplace.

As enteric methane emissions represent a significant portion of the supply chain emissions of many food processors and consumer product good companies that have made public commitments to reduce their GHG emissions, payments to producers for creating methane reductions could become commonplace in the future. However, the industry should be cautious of approaches that limit market access for cattle producers. For example, consider a scenario where a feed additive that consistently reduces enteric methane emissions becomes available and FDA approved in the U.S. and Company X requires all cattle within their supply chain to be fed the feed additive or they cannot be marketed in their supply chain.

In such a scenario, Company X would likely create such a mandate so they could meet their own GHG commitments by forcing the adoption of a potentially costly technology by cattle producers. However, while Company X would seek to claim the GHG reduction, the reduction was created by the cattle producer. Thus, by not compensating the cattle producer for the asset they have created (the methane reduction), Company X would in a way be undercutting and underpaying for an asset via mandating its creation that requires farmer adoption in order to sell their products to Company X. While such language may seem extreme, it is a potential risk for the future. Creating transparency on how the costs of feed additives can impact cattle feeding margins via tools such as AgNext’s FACT for beef can hopefully better understand the risk and potential reward for value creation for cattle feeders by mitigating enteric methane emissions.

Sara Place Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Feedlot Systems